|

| Human body, lymphatic system, livescience |

***

Two separate scientific reports give concrete information on how the brain and immune system interact . One report finds that the brain is directly connected to the immune system; the other that the immune system may contribute to schizophrenia via a gene called C4.In June 2015, researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine revealed findings that the brain is directly connected to the immune system by vessels previously thought not to exist (ScienceDaily). Scientific American also reported on this discovery, saying

As early as 1921 scientists recognized that the brain is different, immunologically speaking. Outside tissue grafted into most parts of the body often results in immunologic attack; tissue grafted into the central nervous system on the other hand sparks a far less hostile response. Thanks in part to the blood-brain barrier — tightly packed cells lining the brain's vessels that let nutrients slip by, but, for the most part, keep out unwanted invaders like bacteria and viruses — the brain was long considered "immunologically privileged,” meaning it can tolerate the introduction of outside pathogens and tissues. The central nervous system was seen as existing separately from the peripheral immune system, left to wield its own less aggressive immune defenses.Scientific American describes the previously-understood separation between the lymphatic system and the brain:

The brain’s privilege was also considered to be due to its lack of lymphatic drainage. The lymphatic system is our body's third and perhaps least considered set of vessels, the others being arteries and veins. Lymphatic vessels return intracellular fluid to the bloodstream while lymph nodes – stationed periodically along the vessel network – serve has storehouses for immune cells. In most parts of the body, antigens – molecules on pathogens or foreign tissue that alert our immune system to potential threats – are presented to white blood cells in our the lymph nodes causing an immune response. But it was assumed that this doesn’t occur in the brain given its lack of a lymphatic network, which is why the new findings represent a dogmatic shift in understanding how the brain interacts with the immune system.

Protecting us against disease, the immune system is an important function of the lymphatic system, which also includes bone marrow, the spleen, and the thymus.

Interaction between psychological processes and the nervous and immune systems of the human body, called psychoneuroimmunology, has been recognized by physicians since the mid-1800s. Common examples are stress causing a headache and the placebo effect.

This month the MIT Technology Review published Immune System Offers Major Clue to Schizophrenia. For so long schizophrenia, which "strikes in late adolescence or early adulthood, sending previously high-functioning individuals spinning into psychosis and often leaving them with devastating cognitive deficits (MIT)," has been a black box. We know it only by its devastating effects. This study finally sheds some light:

The C4 gene participates in what’s known as “the complement cascade,” a process by which the immune system marks tumors, viruses, or dying human cells for elimination and removal. What Stevens, along with Stanford biologist Ben Barres, found was that the complement cascade also plays a novel role in brain development early in life. Specifically, the system helps to “prune” unneeded or unused synaptic connections, sculpting the brain into a more efficient structure. Stevens demonstrated that complement molecules were serving as an “eat me” signal, summoning tiny cells in the brain known as microglia to converge on unused synapses and prune them away.

***

|

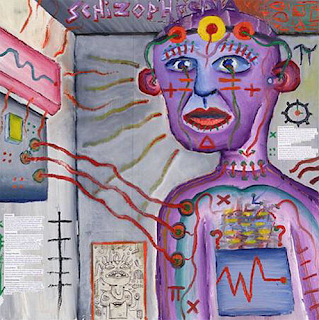

| Artistic view of how the world feels with schizophrenia, Wikipedia |

***

-- Marge

No comments:

Post a Comment