|

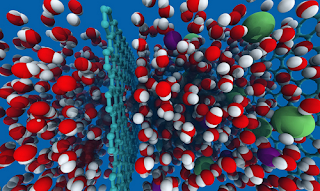

| Lockheed Martin's Pefrorene graphene filter, Industry Tap |

***

While we hear a lot of news about the long-standing drought in California and the subsequent water shortage, California is just one of many other places on Earth that must deal with a shortage of drinkable water.Although passive systems, such as the Warka Tower, are intriguing, there is often some factor that limits application. In the case of the Warka Tower, if the relative humidity is low, there will be no water in the atmosphere to condense. Since the ocean offers a large supply, it looks like the most viable way to get drinkable water is desalination. Keep in mind that not all water needs to be drinkable--we use water for many tasks that don't require the purity of drinking water. For example, there's graywater. Here's How 10 Western Cities Are Dealing with Water Scarcity and Drought.

The International Desalination Association quotes the United Nations:

Of the world’s water, 97.5 percent is salt water from its oceans. Only 2.5 percent is fresh water. Of that 2.5 percent, approximately 69 percent is frozen in glaciers and ice caps, leaving less than 30 percent in fresh groundwater (swamps account for another 1 percent).Humankind has been desalinating water for a long time; the American Chemical Society cites a paper published by Arab chemists in the eighth century. Until the 20th century distillation was the method used. Now the preferred method is reverse osmosis which, in the case of large-scale desalination, is expensive.

Many countries currently have desalination plants in operation; a good example is Israel's Sorek. But despite the engineering economies that the Sorek plant uses, the energy required to push the water through polymer membranes is still high. According to Industry Tap--

In 2011 the US national resources Council reported that the cost of traditional sources of water are from $.90 to $2.50 per 1000 gallons produced. The cost of desalination on the other hand ranges from $1.50 to $8.00 for the same amount of water. These costs prevent some utilities from implementing desalination on a large scale.An energy-saving alternative to the polymer membranes currently being used for filtration are nanoporous graphene filters. ExtremeTech describes one of several methods for mass-producing graphene. Wikipedia's article on graphene describes many other methods. And ScienceDirect has some nice illustrations. The article from Industry Tap quoted above suggests that Lockheed Martin is marketing a graphene product called Pefrorene. In February Reuters reported that Lockheed is testing. Meanwhile, Lockheed suggests it's a done deal.

We wait.

-- Marge

No comments:

Post a Comment